By the mid 18th century, separate communities of Ashkenazim and Sephardim developed in various parts of the Land of Israel. While there had been various Jewish communities in the Holy Land since the destruction of the Temple, the Sephardic community of the “Old Yishuv” owed its genesis to descendants of Spanish exiles who arrived in the years following the great expulsion in 1492. The Ashkenazim, on the other hand, arrived in several waves, the most well-known being the aliyah of the chasidic community on the one hand and those of the misnagdim—disciples of the Gaon of Vilna—on the other. The former began arriving in the mid 18th century while the latter came about a half century later.

The chasidim and perushim (as the misnagdim came to be known) formed their separate communities. Because of the very small size of both communities and the common challenges that they faced, it wasn’t long before there was a degree of intermixing (something unheard of back in Eastern Europe where the chasidic-misnagdic battles were still raging). Another interesting phenomenon is the slow and steady rate of intermingling between Sephardim and Ashkenazim. This was perhaps more evident among the chasidim (who as I mentioned in previous articles adopted a modified Sephardic rite based on the writings of the Arizal, who was himself of both Sephardic and Ashkenazic parentage).

The great chasidic leader R’ Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk, who in 1777 led a group of 300 chasidim to Eretz Yisrael, believed in melding the various Jewish communities in the Holy Land together and married off his son Moshe to a respected Sephardic family. The bride’s dowry was 800 Turkish groschen (a large sum for the time). He also married off his daughter to the Abulafia rabbinic family from Tiberias. Perhaps more interestingly, even before that, Rabbi Gershon of Kitov (1701-1761), brother-in-law of the Baal Shem Tov (founder of the chasidic movement), married his daughter to the son of the Sephardic Chacham of Hebron.

Rabbi Gershon of Kitov was an interesting personality. When his more famous brother-in-law began propagating his ideas, Rabbi Gershon became a vociferous opponent. He eventually came over to his side and became a chasid himself. Rabbi Gershon made aliyah in 1742, making him the first immigrant of the chasidic aliyah. He initially settled in Hebron, which had a small community consisting solely of Sephardim. He was treated with great reverence there and spent most of his time studying in the study hall. He grew dissatisfied, as he wrote in a letter: “Although the Sephardim treat me with great respect I have not found anyone here who is like me in nature.” He eventually moved to Jerusalem, where his wife passed away. He was encouraged to remarry by the local Sephardim who offered him a match from one of their own but he demurred, claiming in a letter that he was unused to their ways and temperament. In that same letter, interestingly enough, he mentions that his daughter Esther was engaged to marry the very learned son of Rabbi Mordechai Rubio, the Sephardic Chacham of Hebron.

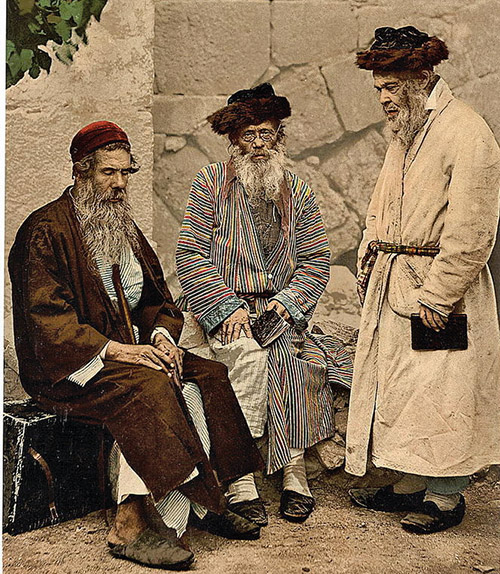

As Mordechai Eliav writes in his article on inter-ethnic Jewish relations in Eretz Yisrael of the 19th century (heb.), “Between the Sephardim and the Ashkenazim [in Eretz Yisrael] there were differences in almost all aspects of life. The differences were not in small part as a result of each one’s way of life and the influence of their respective countries of origin, the Ashkenazim from Christian lands and the Sephardim mostly from Islamic countries. The differences between them was starkly evident in their encounter with each other in the Holy Land. Each one looked at the other as strange. Although undoubtedly in the beginning these differences translated into quarrels and conflicts that seemed unbridgeable, eventually the realities of life forced the two communities to coexist, cooperate and mutually respect each other.”

The aforementioned conflicts often had an economic component. The communities were more often than not poverty stricken and relied on the generosity of their brethren in the Diaspora. In order to keep the funds coming, the Sephardic community had originated the system of shadarim, or charity collectors. As Matthias B. Lehmann explains at length in his book “Emissaries From the Holy Land,” Ottoman-ruled Palestine was something of a backwater province. Ruled by corrupt governors called pachas, the Jewish communities were not given too many incentives to flourish. Nonetheless, Israel continued to be the destination of many Jews. Due to the fact that infrastructure was poor and corruption was rampant, poverty often reigned supreme. This necessitated a system whereby emissaries from various communities would undertake journeys in order to raise much-needed funds.

The Jewish community that would come to play a pivotal role in this centralized system was the Sephardic community of Istanbul. The impetus for the founding of the “Committee of Officials for the Land of Israel” was the appalling situation of the Ashkenazic community in Jerusalem in 1720 when the Muslim authorities destroyed the synagogue and living quarters of the Ashkenazim. These particular Ashkenazim, who made up the majority of their kind in the city at that time, were disciples of a mystical messianic rabbi named Judah the Pious (not to be confused with his medieval namesake).

They had arrived en-masse to Jerusalem in 1700. By the second decade of the 18th century, they had so mismanaged their funds and incurred a mountain of debt that the entire enterprise was on the verge of imploding.

It was at that point that the Sephardic Jews of Istanbul swooped in to bail them out by founding the aforementioned organization (known by their Hebrew name “Pekidei Kushta.” This factoid is ironic in light of the later discord between the two communities—chiefly the oft-cited accusation by Ashkenazim that the Sephardim only look out for their own).

It was only natural for the Istanbul Jews to assume responsibility—and, more importantly, to see results—as they were close in all senses to the main seat of imperial power.

Where did the bailout money come from? In large part from taxes imposed on the community (of Istanbul) members. To be sure, this was met with some resistance by certain community members, which necessitated a declaration from Istanbul’s leading rabbis that anyone who shirks his payment duties, “authority is granted to detain him and he can be taken by force…his refusal is the cause of the destruction of Jerusalem.” Fines and imprisonment were also options in a community that wielded significant autonomy.

The shadarim were a colorful bunch. Several of them went on to write diaries and descriptions of their encounters while traveling. One of them in particular left an extensive record of his activities, Rabbi Hayyim Yosef David Azulai, better known as the Chida (1724-1806). He was born in Jerusalem, in 1724, on his father’s side the scion of a well-respected Sephardic family that settled in Hebron. His mother was the daughter of Rabbi Yosef Ben Pinchas Biala who came to the Holy Land with the Ashkenazic mystic Rabbi Yehuda Chasid in 1700.

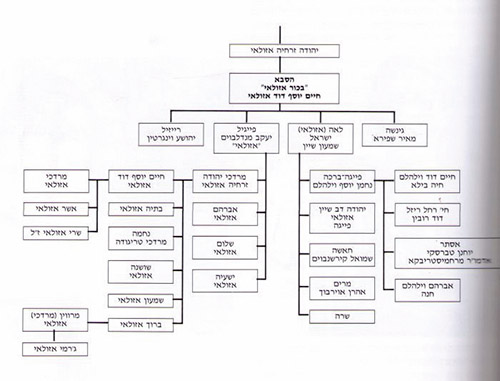

Azulai would become the progenitor of many of Jerusalem’s most prominent Ashkenazic families. I am sure you’ve heard of the famous Mandelbaum Gate that used to divide Jerusalem between its Jordanian and Israeli zones before 1967. What is less known is who this Mandelbaum was exactly.

According to Wiki, “The crossing was named after the Mandelbaum House, a three-story building that stood at that location from 1927 to 1948. The house was built by a Jewish merchant named Simcha Mandelbaum, who had raised his ten children in the Old City but who needed a home with more space to accommodate his married children and guests. Rather than build in more populated areas like Jaffa Road or Rehavia, he chose to build on a lot at the end of Shmuel HaNavi Street, near the location of the Third Wall from the time of King Agrippas. Although Mandelbaum wanted to set an example for other Jews to build in the area and expand Jerusalem’s northern boundary, the Waqf owned large tracts in the area and forbade Arabs from selling any more land to Jews, so the house stood alone…”

Simcha Mandelbaum’s brother Yaakov, who was born in Minsk, White Russia, appended to his name the surname “Azulai” and was sometimes known as Yankel Azulai. He was proud of his marriage to Faiga, the daughter of Bekhor Chaim Yosef David Azulai, who claimed direct descent from his namesake (although this claimed descent is questionable. The true identity of Bekhor C.Y.D. Azulai—who was apparently born in Russia(!)—deserves a separate essay). The family, which was apparently Sephardic, had obviously acculturated many Ashkenazic traits (as evidenced by the typical Ashkenazic names it chose for its children). Many of the descendants of this family dropped the name Mandelbaum altogether and adopted the surname Azulai.

They are the progenitors of many of Israel’s most prominent Ashkenazic families, including the brothers Rabbi Atik as well as several chasidic admorim, having brought the wish of their spiritual forebear, Rabbi Mendel of Vitebsk, to fruition at least to some degree.

The author runs Channeling Jewish History. He is an independent researcher of Jewish history—with a particular interest in the fluidity of Jewish subethnic and religious identity in the Medieval and modern periods—and a translator of Hebrew text (he also misses being a scholar-in-residence during non-COVID times). He can be reached at [email protected].